Stop telling Black people to pray for Donald Trump, by Andre Henry

10/8/2020, 6 p.m.

Donald Trump is a sick man.

Last Friday, as the president went to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to be treated for COVID-19, some Americans responded to the news of the president’s condition with delight, oth- ers with doubt and yet others with death wishes. Most of the rest insisted that the American people — especially Christians — have an obligation to pray for the president’s speedy recovery.

As someone reared in a Christian tradition, I’m well aware of the many Bible passages that urge people to love and pray for leaders, and sometimes even their enemies. As a Black activist, however, I’m also well aware of how those passages have been turned against op- pressed people, forbidding the expression of legitimate human emotions in response to violence and coercing us to silently comply with our own harm.

Because of this history, I think it’s justifiable for Black Americans to decline to hasten to prayer intercession for the president. Refusing to pray for our anti-Black oppressor-in-chief is logical, human and prophetic.

Imagine if the president were an antebellum plantation overseer who had fallen ill. The enslaved in his work camp would no doubt be told to pray for him. Many probably wouldn’t — at least not for his speedy recovery — because they know that the sooner the overseer recovered, the sooner he’d be breaking their teeth and ripping flesh from their backs. It would be illogical for the enslaved to wish for their captor’s good health.

The plantations that survived have largely been turned into backdrops for wedding photos, but America’s anti-Black caste system — and the violence thereof — has yet to undergo a similarly genteel transformation. We still suffer the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery and the gruesome execution of George Floyd. We wonder as the only officer to be indicted in the shooting of Breonna Taylor was charged for the bullets that missed her.

President Trump was elected to defend the American caste system, in which white life matters most. This is why he couldn’t denounce white supremacy in his first presiden- tial debate with Democrat Joe Biden, though the opportunity was handed to him on a platter. Instead, he told violent white nationalists to “stand by.”

You may begin to understand why some Black people were not anxious to get him back to the Oval Office. The sooner he’s back at work, the sooner Presi- dent Trump can demand that schools adopt whitewashed his- tory curricula through his “1776 Commission.” The sooner he’s well, the sooner he can release federal agents to snatch Black Lives Matter activists off the streets in unmarked vehicles, as they were in Portland. The sooner he recovers, the sooner he can continue to refuse to take seriously a pandemic that has disproportionately killed Black citizens.

As long as President Trump is quarantined, we can’t hear him denigrating “BLM” by uttering “Antifa” — an organization that doesn’t even exist — in the same breath. The Kyle Rittenhouses and Proud Boys can’t hear him promise that a regime of violence waits to support them as they deputize themselves as the protectors of white order.

People who believe there’s some apolitical lens through which we should view the president’s illness are fooling themselves. This isn’t the host of “The Apprentice” who has fallen ill, but one of the most powerful men in the world, one who has proved himself an ally to white supremacist violence.

It’s natural for Black people, who have experienced President Trump’s presidency as an exis- tential threat, to be relieved or even to feel joy at the thought of that threat being removed. It’s an abuse of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures to censor these emotions because the Bible holds sacred space for them. “Let his days be few; and let another take his office,” one psalmist prays of his enemies, a prayer some conservatives wryly prayed for President Obama.

Another psalmist sings to the Israelites’ Babylonian captors: “Doomed to destruction, happy is the one who repays you according to what you have done to us.” The Hebrew sage in the Book of Proverbs writes, “When the wicked perish there are shouts of joy,” and when the writer of Revelation imagines liberation from Roman rule, he envisions Caesar, symbolized by “The Beast,” being thrown into a lake of fire as angels shout “Hallelujah!”

These biblical passages may not represent the highest ideals of Christian love toward one’s enemies. However, it’s manipulative to pretend that the only thing the Bible has to say about responding to oppression is “Turn the other cheek.”

The fact that some supplicants ask or imagine God to afflict wicked rulers—or worse—doesn’t mean Christians should automatically do the same. But it must at least suggest God can hold space for those emotions in prayer. And if God holds space for such expressions of raw human emo- tion, then who are we to shame people for feeling them?

The Bible at times encourages us not to intercede for others. “How long will you mourn for Saul,” God asks the prophet Samuel, referring to the deposed king of Israel, “seeing I have rejected him from reigning over Israel?” As the Israelites await deportation by Nebuchadnezzar’s imperial forces, God tells the prophets not to pray for Israel’s king or people because it won’t make a difference: “Do not pray for this people or offer any plea or petition for them, because I will not listen.” It was time for them to face the consequences of their actions.

No one would be gleeful about the president’s illness had he not done everything in his power to make us vulnerable to it, including lying about its severity. As Naomi Klein put it in a recent interview, “This is the epidemiological equivalent of a mass shooting where the shooter opens fire on the crowd and then turns the gun on himself. ... This is not a tragic accident, this is a crime scene.”

Similarly, President Trump has sown the wind and reaped the whirlwind. It’s a prophetic act to commend him to the hands of God.

Even if one concedes that anything can happen with prayer, that President Trump could have some Dickensian transformation and wake tomorrow morning ready to give Bob Cratchit a raise and send Tiny Tim’s family a Christmas ham, that wouldn’t oblige those most harmed by his presidency to become custodians of the impossible. It’s the Holy Spirit’s job to soften hardened hearts, not the job of the oppressed.

So if I or any other Black person chooses to pray for the president, we’re not limited to choose to wish for his health or his death. There’s an array of options, including “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done.”

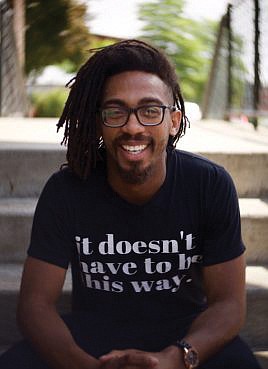

The writer is program manager for the Racial Justice Institute at Christians for Social Action. He writes a weekly email and hosts a podcast called “Hope & Hard Pills,” sharing insight on anti-racism and social change.