VCU’s 2022 ‘Common Book’ further exposes Richmond’s racist past, by Chip Jones

9/1/2022, 6 p.m.

Parking in front of a massive stone clubhouse, I was ready to enjoy an evening visit with a book club in the suburbs.

You may know the drill — sip wine, nibble cheese, and, after 20 minutes or so, finally start discussing the book of the month.

Don’t get me wrong. I love book clubs and the good people who take the time to read — and really ponder — new works.

Since the 2020 publication of “The Organ Thieves” — my in-depth history of Virginia’s controversial, racially-charged first heart transplant that took place 1968 — I’ve come to more fully appreciate the invaluable role that bibliophiles play in America’s literary life.

My nonfiction account of the long, troubling history of the mistreatment of Black Richmonders (and their burial grounds) by the old Medical College of Virginia (now VCU Health) has been selected by Virginia Commonwealth University as its 2022 “Common Book.” That means a copy of the book is given to each first-year student to read and to the faculty to use in their course work as they see fit.

“The Organ Thieves” probes and exposes the systemic racism in Richmond in the 1960s and 1970s — especially in health care, law and politics. Perhaps that’s why it has drawn widespread interest from RVA area book clubs.

As a writer, I am an inveterate observer in these book club settings. I enjoy discovering each club’s DNA, so to speak. For example, folks who meet in churches, synagogues and libraries tend to hold more serious discussions than those who start their meetings with drinks and appetizers.

I think of this latter group as a kind social hybrid – a bit of the English drawing room (hello, Jane Austen) and “Cheers,” where everyone knows your name and what you’re reading. But whether drinks are served or not, the clubs’ readers often share a common theme by serving up new insights to authors.

When it was time to start the Chesterfield clubhouse meeting, the host motioned for me to sit in front of the fireplace. After nearly two years of discussing my book in virtual settings, it felt good to re-gather with people in a a real, live book club — at least at first.

People didn’t appear in boxes like guests on the “Hollywood Squares.” They were mostly women, with a few male partners in tow. As the room hushed and the host introduced me, I realized there was another advantage to meeting in person: I didn’t have to peer into my MacBook’s camera to make eye contact.

Only now, all eyes turned toward me. Gulp! I wonder if there was cheese hanging from my mouth...and would I be up to answering their questions?

Still, taking a sip of red wine, I settled back to enjoy myself.

The next morning, I awoke feeling mentally drained. But why? It wasn’t because I drank too much. The queries came too fast and furious for that. Important questions such as, “Is racism still ingrained in our health care system?” (Yes).

“Was the family of the man who gave up his heart ever financially compensated for the unauthorized transplant operation?” (No).

“Has VCU issued a public apology?” (Not yet).

Great questions all – so great, in fact, that they led to a sleepless night. Meeting in person may have erased the distance of a Zoom call, but there would be an emotional price to pay: I had to be more present.

The first spark of emotion was lit by a gregarious woman who said her father was a prominent judge here in the 1960s. As a teenager, she was an avid newspaper reader, she said. So, after reading my book, she was surprised to learn how little she knew about Virginia’s first heart transplant – and the Black man who had his heart taken from him without any prior consent or his family’s knowledge.

He was a factory worker named Bruce Tucker.

“I didn’t sleep for two nights after I read about Bruce Tucker!” she said.

“I’m sorry.”

“Oh, don’t be sorry!” she reassured me. “No one should sleep well after reading your book.”

Other readers expressed their own degrees of outrage and disgust over what had happened to Mr. Tucker and his family at the hands of the white medical

and legal establishment in the former Capital of the Confederacy. Most agreed that the transplant surgeons acted too quickly in their quest to perform what was then a highly experimental procedure on someone in a coma.

One book club attendee, a former nurse, offered a tentative defense for the transplant surgeons who raced to be first back in the day.

“Competition helps us make medical advances,” she said.

It was a fair point – although I didn’t necessarily agree that it applied in this case. But I kept my thoughts to myself. It was their turn to talk and I was their guest.

As any counselor or therapist can attest, listening – really listening – can be exhausting. It may even disturb your sleep.

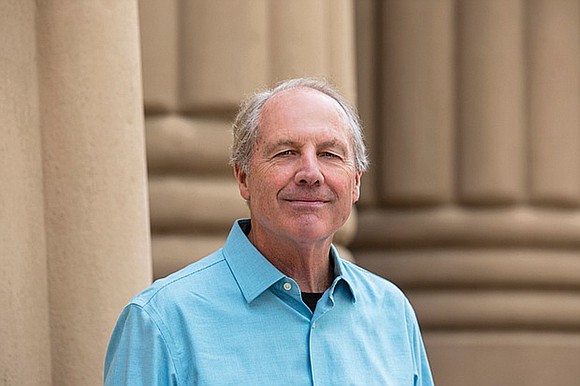

Chip Jones is the author of “The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South” winner of the 2021 Library of Virginia Literary Award for Nonfiction.