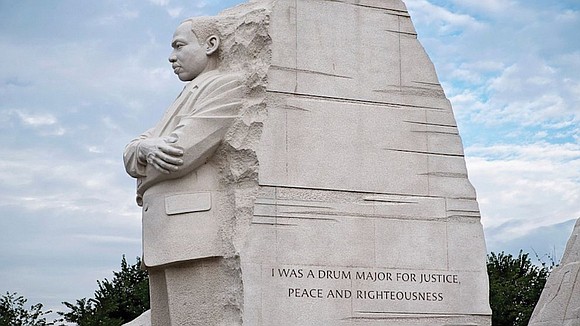

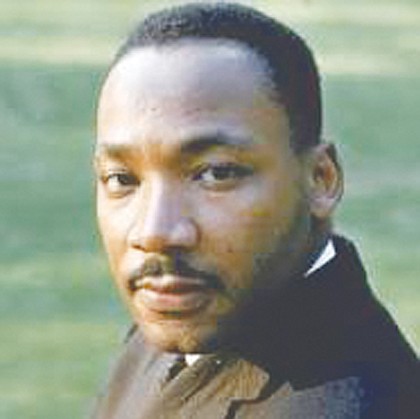

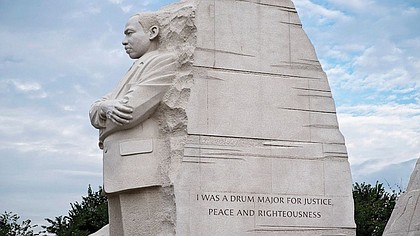

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

4/6/2018, 7:35 a.m.

Fifty years after the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, the world honors his legacy and leadership in civil rights activism to bring freedom, equality and justice to all people.

Dr. King believed in the inherent worth of all people and sought through nonviolence to fight against racism, poverty and militarism, all barriers to living in what he called the “Beloved Community.” The “Beloved Community,” he detailed, is a place where all people can share in the bounty of the Earth.

On the anniversary of his death, the Richmond Free Press asked five area thought leaders:

Have we achieved Dr. King’s “Beloved Community”?

The Rev. Phoebe A. Roaf, rector, St. Philip’s Episcopal Church

As we remember the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, have the goals he so powerfully articulated been accomplished?

One of the concepts developed by Dr. King is the “Beloved Community,” a future when all needs will be fulfilled as humanity shares Earth’s resources. In the Beloved Community, poverty, bigotry and war are eradicated.

Dr. King was convinced that the Beloved Community could be achieved. He devoted himself to promulgating this vision of God’s kingdom here on Earth. Others, inspired by his vision, have pursued Dr. King’s legacy to the present time.

Yet, considering the state of affairs in the city of Richmond, the Commonwealth of Virginia and the United States, we have fallen woefully short of the Beloved Community that Dr. King imagined. In Metro Richmond, men and women stand on street corners holding handmade signs requesting assistance. Public schoolteachers labor in poorly maintained buildings. The nightly news includes stories of violent confrontations between loved ones as well as total strangers. Mass shootings have become commonplace events. Income inequality continues to widen in the United States.

These conditions indicate the Beloved Community has not been achieved. Fifty years after Dr. King’s death, his vision remains a dream. However, why are we surprised at this fact? My faith teaches that the Beloved Community cannot be fully experienced this side of the grave. All of our needs will be fulfilled when our souls are reunited with God.

I face the future with a sense of hope because I do not carry the burden of perfecting society alone. Many others share the load. For example, the March for Our Lives events on March 24 demonstrate that today’s youths are just as committed to the Beloved Community as their counterparts who spearheaded the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s.

Dr. King dedicated his life to making our country a better place. What is asked of each of us is to do the best we can, as imperfect as our efforts may be.

At the end of Dr. King’s life, I envision the Lord telling him, “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Matthew 25:23). The question is not whether we have accomplished the Beloved Community. Rather, the question is when you and I reach the end of our lives, will God say the same to us?

Dr. M. Imad Damaj, professor, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, VCU School of Medicine

For many, the vision of a “Beloved Community” as envisioned by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., died when he was assassinated in 1968.

I was a 7-year-old living in Beirut, Lebanon, at that time. In 1985, I departed my country of birth, leaving behind a terrible civil war for a hope for a better future and career.

In 1991, I landed in Richmond after my graduate studies in Paris. Richmond gave me and my family so much and I am so grateful and indebted to that community. Having vaguely heard of Dr. King and other giants of the Civil Rights Movement like Malcolm X at my arrival, I quickly realized that I am enjoying the fruits of the civil rights struggle. A movement that was essentially a struggle for the establishment of basic human rights for African-Americans changed America’s racist immigration laws and resulted in the Immigration Act of 1965 that lifted many of the race-based immigration restrictions that allowed me and many others to settle here.

While tremendous progress has been made since the 1960s toward establishing our Beloved Community, a lot of challenges remain — an increasing gap between hopes and realities of many millions of Americans; mass incarceration; a seemingly unending stream of police shootings; and an alarming increase in poverty.

In a time of rising nationalism, bigotry and hate, the vision of the Beloved Community can feel as impossible as ever. But for me and for many people, that vision still guides the work that we do and the hope that we carry.

I came from a part of the world where people allowed themselves to be divided by hate toward one another’s religion, tribe or class. I came to the United States 27 years ago with many myths, misconceptions and lies about race, class, peace and much more.

If we wish to free ourselves from these toxic beliefs that afflict our hearts and souls, we need to shine the light on our brokenness and transform ourselves to help build a community that reflects our ever-increasing wholeness and dignity.

For those who say that we have to “give it time,” I remind you of the words of Dr. King in his last sermon: “Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of dedicated individuals who are willing to be co-workers with God.”

Dr. Oliver W. “Duke” Hill Jr., professor of experimental psychology, Virginia State University

Dr. Martin Luther King’s vision of the “Beloved Community” referred to a society based on justice, equal opportunity and love of one’s fellow human beings.

Has Dr. King’s vision been achieved? The answer is obvious, given the testimony of police shootings, the Trump election, Charlottesville, the growing prison-industrial complex. The list could go on and on.

However, Dr. King was an optimist, and I, too, think there is reason for optimism, despite the long, regressive list of counter-examples above.

The scenes of torch-wielding neo-Nazis from Charlottesville and the mayhem they fomented reminded many of the violence and atrocities perpetrated by white supremacists in the 1950s and led many to conclude that we are now living in an even more hyper-racialized time. But having lived through those times, I can unequivocally say that we are not back there by a long shot.

My father was a civil rights lawyer, and we got threatening phone calls every night. Whenever my father was out at night, my mother would wait for him on the back porch with a gun in her lap (even though I don’t think she knew which end was which). A cross was burned on our yard in Richmond, and I don’t even think it made the local news.

It took recruiting from all over the United States and Canada to assemble 200 white supremacists in Charlottesville, and their marginalized status was highlighted by the resistance in that community and the outrage expressed all over the country and around the world — with the exception of the leader of the free world! In the 1950s, it was the non-white supremacists who were on the margins, and the white supremacists were the ordinary citizens — the police, the judges, the teachers. Black people shot by the police, or those who just “disappeared,” received little or no notice from the mainstream media.

I don’t know of many African-Americans who thought we had gotten to a post-racial society, even though many white liberals were stunned at the overt racism evoked by the Trump campaign (America still racist? Who knew?!).

The Charlottesville Nazis and their ilk are scary, and the Trump zeitgeist has allowed them to crawl out of their holes. However, looking back over the long span of my life, I do have to acknowledge that things have changed for the better. The white supremacists are now on the margins.

The racism, sexism, homophobia and xenophobia emerging since the last presidential election has been countered by a new sense of activism that is rising up. I’m sure Dr. King would be heartened by the youth leadership exemplified by the Black Lives Matter, #Never Again and #MeToo movements that are transforming our country. The spectacle of the Trump presidency also is driving record voter registration numbers and motivating scores of women and people of color to run for public office.

In quantum physics, there is a phenomenon known as a phase transition in which an incoherent system shifts instantaneously into a coherent state. This phase shift occurs when a small but critical mass of particles start to exhibit coherence, and then it suddenly spreads to the whole system. As we observe the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination, I would like to think of our society as being on the cusp of a phase transition and that the Beloved Community is not as far away as it might appear.

The writer is the son of the late Oliver W. Hill Sr., the noted Richmond civil rights attorney whose work helped end the doctrine of “separate but equal” in U.S. public education, bring equal pay to African-American teachers in Virginia and further voting rights among other landmark legal gains.

Dr. John V. Moeser, emeritus professor of urban studies and planning at Virginia Commonwealth University and a retired senior fellow of the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement at the University of Richmond

If Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. were alive today and lived in Richmond, what would he say about this place?

One thing for sure, he wouldn’t call it a “Beloved Community.” Far from it. And yet, precisely because of Richmond’s uniquely troubled past, I can hear him challenge us to do things that no other city has done.

What place could better illustrate redemption and where all of God’s people live together than Richmond? What better place than this place, once the capital of the Confederacy, the center of the interstate slave trade, a place of unimaginable suffering that continued long after the Civil War and deep into the 20th century when black neighborhoods were destroyed by highways and urban redevelopment and where the human spirit was crushed because of unfulfilled promises to undo what was done?

But, what if? What would Richmond look like if the people of Richmond mustered the vision, the courage, the will and the involvement to create a Beloved Community? What would it look like?

I think it would be a place where citizens are willing to plunge the depths of their history openly and honestly, learn from it, and use it to bring together people who, for too long, have been estranged from each other to become friends and neighbors.

A Beloved Richmond would be a place where the slave district, in its entirety, would be forever preserved as a sacred space and designed to induce reverence.

A Beloved Richmond would erect a permanent cover over that segment of Interstate 95 that divided Jackson Ward. It would be landscaped with grass and flowers and support statuary that would memorialize the people who made this place more than a black neighborhood, but rather a separate city.

A Beloved Community would be comprised of mixed-income neighborhoods where children of all races and backgrounds live together and attend safe schools together. It would be a city of economic promise where workers are paid living wages and encouraged to create their own businesses. It would be a place where ZIP code no longer determines one’s future, where 20-year differences in life expectancy between East Richmond and West Richmond no longer exist.

If Richmond were to speak honestly about its tragic history — not evade it or reinterpret it — and if we opened up about our own personal histories, we would discover that all of us have been scarred one way or another. Had it not been for the intervention of family, friends, even strangers whose love was unconditional, most of us — white and black alike — would be lost today.

Just as we must forever remember the injustices experienced by African-Americans, we must forever celebrate their heroic endurance, their relentless resistance and their peaceful pursuit of civil rights. What could have been a bloodbath turned into a nonviolent crusade comprised largely of young people whose wounds — and their deaths — never gave way to retribution. They embodied the very essence of Dr. King’s Beloved Community.

Richmond, more so than any city in the nation, has an opportunity to use history constructively to become a place of hospitality, a place that welcomes the stranger, a place for all of God’s people, where residents of Chesterfield, Henrico, Hanover and Richmond alike call home. We could make concrete what Dr. King envisioned.

It is only when Richmond becomes a good city that it becomes a great city.

Sen. Jennifer L. McClellan, chair of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission in Virginia

Where are we in achieving Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of a “Beloved Community?” Where do we go from here?

As chair of the Virginia General Assembly’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Commission, I’ve been exploring those questions as moderator of a series of community conversations in the dozen Virginia jurisdictions that Dr. King visited in the 1950s and 1960s.

As described by the King Center in Atlanta, in the Beloved Community, poverty, hunger and homelessness will not be tolerated because international standards of human decency will not allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood. Love and trust will triumph over fear and hatred.

To gauge where we are today, it’s helpful to look at the 1968 Kerner Commission Report, issued just more than a month before Dr. King’s death. Examining cultural and institutional racism in the United States, the report concluded with a stark warning: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

Dr. King called the report a “physician’s warning of approaching death, with a prescription for life.”

Indeed, the report echoed the framework Dr. King laid bare in his 1967 book, “Where Do We Go From Here?” But nobody listened.

The backlash to the report and the civil rights gains made by African-Americans in the 1950s and 1960s was immediate, culminating in the racially exploitative “Southern Strategy” that elected President Richard Nixon. This backlash was reminiscent of the Jim Crow laws enacted at the turn of the 20th century that struck at the socioeconomic gains former slaves made during Reconstruction.

Today, we see another backlash to the gains made by African-Americans during the past 50 years, culminating in the election of President Donald Trump and the re-emergence of explicit white supremacy, as seen at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville last summer.

Since 1968, we have seen more African-Americans elected or appointed to office, including the first African-American president. We’ve seen an increase in African-American leadership in the private sector as well, from Hollywood to the C-Suite. Today, more African-Americans have college educations and have seen significant improvement in wages, income and wealth since 1968.

And yet, African-Americans still lag behind white people in each of these categories and face similar disparities in health — particularly life expectancy and infant mortality — homeownership, incarceration and even school discipline.

We still have a long way to go to achieve the Beloved Community. But more than lingering racism and prejudice, the ignorance and indifference to the fact that emancipation and civil rights laws did not magically erase the 400-year impact of slavery and Jim Crow on society as a whole remains an impediment to progress. Only a complete and unvarnished look at American history can provide that understanding.

And if we follow the path to the Beloved Community written in both Dr. King’s book, “Where Do We Go From Here?” and the Kerner Commission Report, we can finally fulfill the promises of American democracy for all Americans.