Confederate group calls for more rebel statues in Richmond

3/16/2018, 7:11 a.m.

By Saraya Wintersmith

As the city of Richmond grapples with whether to remove the statues to Confederates from Monument Avenue, the Sons of Confederate Veterans is calling for more to be built — with signs putting them in context to be placed at the African Burial Ground in Shockoe Bottom.

At a meeting last week with members of the Monument Avenue Commission, members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans’ local unit said three statues should be constructed to honor Confederate women, captured Confederate soldiers and black people who “willing or not, loyally served” the rebels.

“With white men mostly off in the armies, trusted slaves ran or helped white women run the large plantations,” said Robert Lamb, a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans in making the case for a statue to African-Americans in the Confederacy.

“Had the blacks mounted a serious resistance or work stoppage, they could’ve crippled the Confederacy,” he continued. “They didn’t do so. They were an integral part of the heroic struggle against the federals and need to be recognized for that.”

Mr. Lamb and SCV member Harrison Taylor called for the city to develop the acreage in Shockoe Bottom that served as a burial ground for enslaved Africans into a slavery memorial and education site; erect the three new Confederate statues on Monument Avenue; and add signs in Shockoe Bottom putting the new statues and those already situated on Monument Avenue in context. They said no contextual signs should be placed on Monument Avenue.

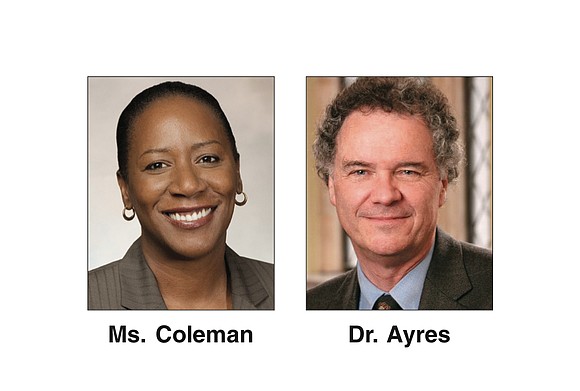

Their hourlong presentation to commission members Ed Ayres, Coleen Butler Rodriguez and adviser Julie Langan was met with stoic silence as they praised the men and states in the Civil War who shed blood to preserve the right to own other human beings.

The Monument Avenue Commission, which was convened by Mayor Levar M. Stoney to determine the future of the Confederate statues on the tree-lined street, has turned to small group “listening sessions” after packed a public hearing last year turned raucous and emotional.

Commission co-chair, Christy Coleman, said last week that no traditionally African-American groups have requested such a session with the commission. And four of nine other scheduled meetings were canceled by the groups requesting them when it was learned they had to provide space for the public, she said.

Early on in the March 7 presentation by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Mr. Lamb repeated the assertion that the Southern states’ secession from the United States was “not about slavery” but because of attempts by the Union to coerce the slave-holding states.

At that point, a man in the audience stood up and walked out of the room, saying, “I can’t take it anymore.”

The audience of slightly more than a dozen people was comprised mostly of gray-haired white men.

“We urge that the context for slavery in general, and the Confederacy specifically, be thoroughly and objectively displayed in Shockoe Bottom to include the site of Lumpkin’s Jail (The Devil’s Half Acre), the Black Burial Ground and the sites for the Goodwin and Omohundro jails. … Context for the statues should be provided here and not on Monument Avenue,” Mr. Lamb said.

He said private money should be secured to finance exhibits on topics such as references to slavery in U.S. Constitution and the Bible, the evolution and timeline of slavery throughout the United States, the role of slavery in the North, slave rebellions and the “sad role of those in Africa in the enslavement of their own race.”

He said removing the statues of Confederate Gens. Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart and Confederates Jefferson Davis and Matthew Fontaine Maury from Monument Avenue would be “tantamount to a cultural crime.”

Mr. Taylor rejected the idea that the monuments, which were built between 1890 and 1929, long after the Civil War and during Jim Crow, were erected in defense and preservation of white supremacy.

“I don’t feel it’s true at all,” Mr. Taylor said. The statues were “put there out of respect to hold society together, which it did.”

In a March 2 public listening session with the Monument Avenue Commission, members of the Richmond Peace Education Center said the Confederate statues should be viewed as a form of “cultural violence.”

They said adding interpretative signs and additional statues would be insufficient to confront Richmond’s history of oppression. The statues’ removal would be a first step to heal racial trauma, group members said, and the persisting racial disparities.

Darien Wyatt, 18, a member of the center’s youth board, said she often hears preservationists falsely equate statue removal with a loss of history.

“There are no statues of Hitler, but do you think (Germany) has forgotten him?” she asked. “Do you think the world will ever forget him?

“When people put monuments up, that shows pride,” she continued. “Does the city of Richmond really want to send the message that we stand strongly behind people who fought for the enslavement of others? People who fought for injustice?”

Responding to a question on what happens after the Monument Avenue Commission submits its recommendations, Ms. Coleman said the people of Richmond have the power to determine how Richmond proceeds.

“The state law is very, very particular and states plainly that you cannot remove or deface or alter (monuments). So if you want something to happen, then the people of this state have to either elect people that will make that decision or put together referendums to get it on a ballot. … It is really will of the people.”