’Intertwined history’

Descendants of the enslaved and their owners on a noted Caroline County plantation are working together to preserve remnants of their shared history that remain on the land

Aldore D. Collier | 5/5/2022, 6 p.m.

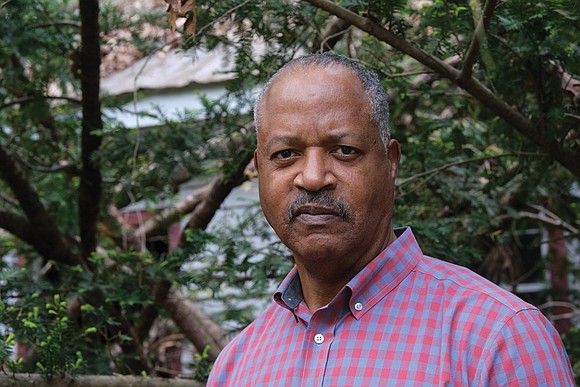

For years, Mike Mines has been fiercely determined to ensure that his two children know what he had not known much of his life — his family’s history.

Kate Chenery Tweedy wanted to know more about her Virginia family’s legacy, including the slaves they owned.

Mr. Mines is Black and Ms. Tweedy is white.

Her ancestors owned his.

Modern technology brought the two of them together in their quest to learn more about their families — both the enslaved and their owners who lived at The Meadow, the legendary Caroline County farm that in modern times gave the world one of the most famous racehorses of all time, Secretariat.

“I want my kids to get a sense of their own history,” said Mr. Mines, 64, who retired after 30 years with the FBI. “I want to give them a sense of how really bad it was during and after slavery for Blacks.”

Through ancestry.com, Mr. Mines found that his great-great-grandfather, Guy Mines, was enslaved at The Meadow, a 3,000- acre plantation in Caroline County, which is now home to The Meadow Event Park and the State Fair of Virginia.

While doing research on the genealogy site, he unexpectedly met Ms. Tweedy.

“There’s a section on ancestry called ‘Owned by.’And there’s a feature that asked if I wanted to reach out to people doing similar history. And that’s how I met Kate Tweedy,” Mr. Mines said. “She had done extensive research on The Meadow,” he said.

His first contact with her was in 2020. They emailed each other then met virtually on Zoom.

“I gave her my research and she gave me hers,” Mr. Mines said. “We compared notes and agreed to get together after COVID.”

Ms. Tweedy, 70, a retired attorney living in Ashland, had done much more than just research on The Meadow. She wrote a best-selling book, “Secretariat’s Meadow: The Land, The Family, The Legend.”

The book was made into a popular movie in 2010 featuring John Malkovich, Diane Lane and Scott Glenn. Ms. Lane played Ms. Tweedy’s mother, Penny Chenery, who bred and owned Secretariat. The famous thoroughbred in 1973 won horseracing’s coveted Triple Crown — the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont Stakes. Some of the records established by Secretariat still stand 49 years later.

“When I was doing research, I found out about the plantation and slavery,” Ms. Tweedy said in a recent Free Press interview. “It was a plantation long before it was a horse farm.”

Although tied to the land by ancestry, Ms. Tweedy grew up in Denver and earned a law degree from the University of California, Berkeley. “I was not part of that world,” she said. “I was a Yankee and a westerner. I’m also a member of the Richmond chapter of Coming to the Table.”

That national organization attempts to heal the wounds of racism rooted in America’s history of slavery. She said she has been every bit as compelled as Mr. Mines to find out about those enslaved on the plantation of her ancestors.

“I wanted to find out how many were enslaved on the plantation. It turns out there were 82 people enslaved on The Meadow. They had a policy of not separating families, so no one was sold downriver,” she said.

She was in the middle of her research when she received the surprising message on ancestry. com from Mr. Mines that said, “Hey, I want to know more.”

“So, I sent him my book,” Ms. Tweedy said. “Then we spoke on the phone.”

Both enjoy plowing into research and now make sure they speak at least once a week as they strategize on how to find more details about that part of The Meadow’s history and get special designation for the place where Mr. Mines believes many of his ancestors are buried.

There is an unmarked burial ground on the land, where Ms. Tweedy said she learned the enslaved were interred. A slave cabin also is on the property.

“The Meadow is already a historic site, thanks to Secretariat,” Ms. Tweedy explained. “We’re hoping to get the same designation for the horse groomsmen, the enslaved and the slave cemetery” on the site.

Last fall, Mr. Mines, who lives with his wife in Loudoun County, and Ms. Tweedy decided it was time to move from phone calls and Zoom to a face-to-face meeting.

Several people, Mr. Mines said, questioned his decision to unearth a painful episode and to team up with an offspring of his family’s owners. But Mr. Mines was determined and credits his FBI training with keeping him laser focused.

“For me, it was just the facts,” he explained. “The expected reaction of visiting the plantation where so many of my ancestors toiled from sunup until sundown would be anger and frustration,” he said. “My mission was to identify the place and go back as far as I could and connect those people with my kids. Meeting Kate was a plus. I wasn’t trying to assign blame.”

Mr. Mines, his wife, Beatrice, and their two adult children, Adrian, 32, and daughter, Lauren, 27, drove the hour and a half from his home in Northern Virginia to Ashland to have dinner with Ms. Tweedy and visit The Meadow, located roughly 20 minutes north of Ashland.

“My wife and son were onboard, but my daughter had misgivings,” he said.

Misgivings might be a somewhat mild description of Lauren Mines’ reaction.

“Sitting down and having dinner with a descendant of the family who owned my family didn’t sit right with me,” she said. “It felt wrong to befriend someone who was related to those who treated my ancestors so wrongly. Her family made a lot of money off the work my family put in, and I felt I was owed something from her. But, ultimately, I am glad I went and visited The Meadow. It was surreal.”

Adrian Mines was moved by the visit every bit as much as his sister.

“I was nervous at first, but once I got there and met Kate, it all felt right,” he said. “Kate was phenomenal. She gave us papers that showed lineage and more. She was the vessel that allowed us to put the pieces together. And she wasn’t afraid to talk about the true history of the place and have tough conversations with us.”

In addition to meeting Ms. Tweedy, the highlight was seeing the slave cabin and the burial ground, Mr. Mines said. Much of the area was heavily wooded and both were difficult to find.

“We had to go through six-foot shrubs to get to it,” he said.

But Ms. Tweedy knew the terrain, Mr. Mines said, and guided them through.

Walking around the grounds that bear the unmarked graves of so many of the enslaved at The Meadow, including, possibly, his ancestors, provoked a response in him that he said he never expected.

“When we were standing there, I was almost moved to tears thinking about what they went through,” Mr. Mines said. “It’s one thing reading about your history and another seeing it.”

Visiting the site together, he said, affected both him and Ms. Tweedy.

“We have an acknowledgment of a shared history. A friendship has developed.”

Mr. Mines and Ms. Tweedy now are committed to ensuring that at least a marker or plaque is erected on the road that bisects The Meadow to show that slaves were buried on the land. The two also are brainstorming about how to preserve the slave cabin.

“If we get that (historic) designation, then the cabin can never be torn down,” Mr. Mines said, pointing out that his mission is far from accomplished.

“We can’t restore the cabin; that takes money. But we can try to get it designated as a historical site and then it cannot be torn down.”

The Meadow dates back to 1805 when it was purchased by Ms. Tweedy’s ancestors. Guy Mines, Mr. Mines’ great-great-grandfather who was born in the early 1800s, was enslaved there along with other relatives.

The plantation changed hands numerous times through the years. Ms. Tweedy’s grandfather, Christopher Chenery, purchased it in 1936 to make it a horse farm. Ms. Tweedy’s mother, Penny Chenery, took over in 1968, consolidated many aspects of the enterprise and eventually gave the world Riva Ridge, the phenomenal horse that won the Kentucky Derby 50 years ago this month in 1972, followed by the Belmont Stakes, and Secretariat, who wowed the world the following year.

After Christopher Chenery’s death in 1973, the land was divided and sold to settle the estate’s debts, Ms. Tweedy said.

“There were other siblings and heirs,” Ms. Tweedy said. “My mother kept the horses but sold the land.”

The experience, Mr. Mines said, has given him a deeper understanding of his roots that his parents never discussed because of the pain of slavery. And it has helped him forge a relationship with someone based on a shared history.

The question, he said, is “how do we move forward with an intertwined history, particularly now when history is being diminished?”

Working together to preserve that history is the answer, he said.

Seeing the reaction of his children has made the effort to uncover the past worth it, Mr. Mines said.

“To see where we came from and the work that our ancestors did ... my father put it in perspective,” Adrian Mines said. “And now it’s our job to find out more and then share the story. It’s our turn to share the family legacy to ensure (our ancestors) are never forgotten.”